Parts Distribution: The New MRO Battleground

Aircraft parts distribution is an underappreciated and vital element of the aerospace ecosystem that is rapidly consolidating and experiencing greater influence by Airbus and Boeing.

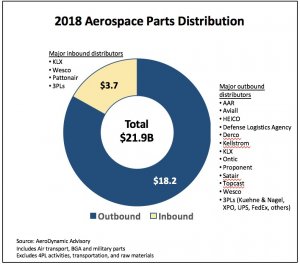

The scale of aerospace parts distribution is impressive, with $22 billion spent annually by civil and military customers. More than 80% is driven by MRO activity--aircraft checks, engine overhauls, modifications, line maintenance and the like--where speed and avilability are often of paramount importance. The balance of distribution feeds production lines.

Distribution boasts two distinct business models. The first is outbound distribution, where the distributor holds inventory and manages the flow of parts from an OEM to its customers. Distributors are often more responsive than OEMs in fufilling low quantity/high mix orders. They also simplify supply chains, as customers can deal with a single distributor rather than hundreds of parts suppliers. This can enable electronic ordering controls, consignment and other value-added services. Distributors also allow OEMs to reduce working capital and to serve customers in emerging regions where they lack logistics capabilities. Despite these advantages, the use of distributors is surprisingly low, with more than 80% of parts by value self-distributed by OEMs.

The other business model is inbound distribution, where a distributor manages the procurement and flow of material into a manufacturing or MRO facility via Kanban and kitting services. Typically, inbound distribution focuses on consumables and expendables, such as fasteners, standards and electrical hardware.

The lofty service revenue ambitions of Airbus and Boeing are well known, and distribution is one area where both have achieved significant progress. In 2006, Boeing purchased Aviall, which at the time was the industry’s largest independent distributor. Last year, Boeing bought KLX, a leading distributor of consumables and expendables.

Airbus responded in 2011 by acquiring Satair, Europe’s leading independent distributor. Impressed with its capabilities, Airbus turned over responsibility to distribute its proprietary parts to the company several years ago.

There are pros and cons to these moves. Aircraft OEMs can provide capital and access to customers. They also can aggregate distributor spending with their own to reduce procurement costs. However, some parts manufacturers are nervous that Airbus and Boeing are acquiring too much knowledge about their aftermarket activities.

Aircraft OEMs aren’t the only players reshaping the distribution segment. In 2016, Kapco Global acquired Avio Diepen, a leading European distributor. The company rebranded as Proponent in 2018. (Author’s note: I serve on the company’s board of directors) In 2017, HEICO acquired a majority stake in Air Cost Control to add to its considerable distribution company portfolio, which includes Seal Dynamics. In August 2019, Platinum Equity announced a deal to acquire California-based Wesco for $1.9 billion and merge it with Pattonair--combining two of the largest “inbound distribution” specialists. And last month, private equity specialist Permira acquired Topcast--China’s leading distributor.

What does the future hold? The answers to three key questions will shape the outlook for aerospace distribution.

1. To what extent will distributors provide greater value? Many airlines are dissatisfied with parts availability, and new tools such as machine learning and advanced aircraft health management data promise to improve parts availability. Can distributors lead the way? Distributors also have an opportunity to provide add-on services such as repair, kitting, niche manufacturing and analytics.

2. Will distributors increase market penetration? With 80% of aerospace parts self-distributed and dissatisfied customers, there is seemingly lots of headroom from greater use of distributors in the future. However, many parts manufacturers deem the cost of distribution services too high or are loathe to introduce an intermediary to customer interaction. One fertile area for distributors is mature and sunset aircraft, where dispersed and unpredictably demand means that most OEMs fall short of customer expectations.

3. What are the next moves for aircraft OEMs? Airbus already consolidated its proprietary spares distribution into Satair’s network. Will Boeing do the same and consolidate the operations of Aviall, KLX, as well as its commercial and military proprietary spares operations? To what extent will they integrate their capabilities into other service offerings, such as Global Fleet Care or Flight Hour Services? How far can they extend their influence before encountering pushback from customers or clients?

Although often an afterthought, distribution has become a dynamic battleground between aircraft OEMs and more capable independents. The outlook is for continued change in this fast-morphing sector.